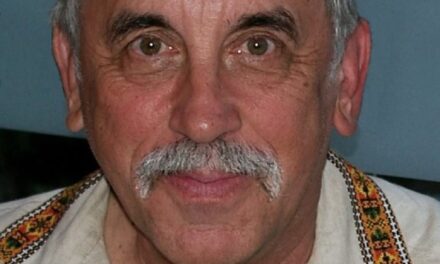

Myroslav Shkandrij for New pathway – Ukrainian News.

At the Front Line: Ukrainian Art, 2013-2019 opened in the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre (Oseredok) Gallery on 26 February 2020. Curated by Svitlana Biedarieva and Hanna Deikun, two researchers from Ukraine currently living in Mexico, the works in this exhibition were first displayed between September 2019 and February 2020 at Mexico City’s National Museum of Cultures of the World.

All the works were created in the years 2013-2019 to express the ways in which artists were affected by political and cultural events in Ukraine – the demonstrations in Kyiv, the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas. Each individual responded to events by creating a personal visual language.

Svitlana Biedareva provides an illustration of vulnerable, child-like figures who grapple with weapons they hardly know how to use, and of nature that turns from nurturing to aggressive behaviour. The central figure is set between two contrasting groups. A group on the left appears to question why they have been given weapons, which they do not know how to use, while a group on the right contains three figures: one holds the weapons helplessly, another turns away from them, and a third, beast-like form moves aggressively towards them.

Svitlana Biedarieva, The Morphology of War, 2017. Photo credit Norbert K. Iwan.

The section of the exhibition entitled “Spaces” contains a series of eight photographs taken in the years 2015-2018 by Yevgen Nikiforov. Entitled “On the Republic’s Monuments”, these illustrate the way sculptures in public places are being transformed by local populations. For example, two photographs of Soviet era monuments reveal the manner in which these were “reinterpreted” in the light of recent developments.

The first photograph captures a monument to the members of the Cheka (the Soviet Extraordinary Commission, namely the Secret Police). Like much of this type of monumentalist art devoted to early Bolshevik leaders, it symbolizes strength and ruthlessness. The two heads, which are grim, overbearing and threatening, have been covered, presumably by local residents, and graffiti has been painted on the pedestal. It says: “Death to Tyrants”, “The Blood of Ukraine is On Them”, and “Executioners.” The second photograph is of the massive titanium warrior woman that dominates Kyiv’s sky-line. She holds aloft Soviet insignia but one of the tanks near the base the monument has been painted yellow and blue, the colours of the Ukrainian flag. Like many contemporary monuments, this one now demonstrates the contested symbolism that unites old and new. Although throughout the country 1,700 statues of Lenin have been removed, many surviving Soviet-era monuments are now being repurposed and endowed with new meaning. In the contemporary context they carry new and sometimes contradictory messages, serve as reminders of a tangled and tragic past, or alert viewers to conflicting interpretations of history.

A powerful message is carried by Lada Nakonechna’s installation. It is a collection of the rocks in the centre of the exhibition’s floor, among which some contain labels such as “junta”, “terrorists”, “separatists”, “fascists”, “Jews”, and “patriots”. These serve as material embodiment of the verbal aggression that has been a part of the war in eastern Ukraine, of the “stones” that are being thrown in the media war, not only in Ukraine and Russia, but also in many Western countries. This simple but effective installation draws attention to the damaging nature of insults, which are often removed from any context and are hurled by people who are not familiar with the targeted individuals – as has frequently been the case in disinformation wars.

The photographs of Yevgenia Belorusets provide some refreshingly personal portraits of Donbas mines and miners. Unexpectedly, perhaps, these are images of women. They show the circumstances and conditions in which workers live and go about their work, but focus primarily on the individual’s face and body. In this way they highlight the vulnerability of each human being. This is a leitmotif of the entire exhibition, which seeks to provide viewers with the viewpoint of the ordinary person who must live through a time overloaded with contradictory, often angry messages, confusing situations and conflicts.

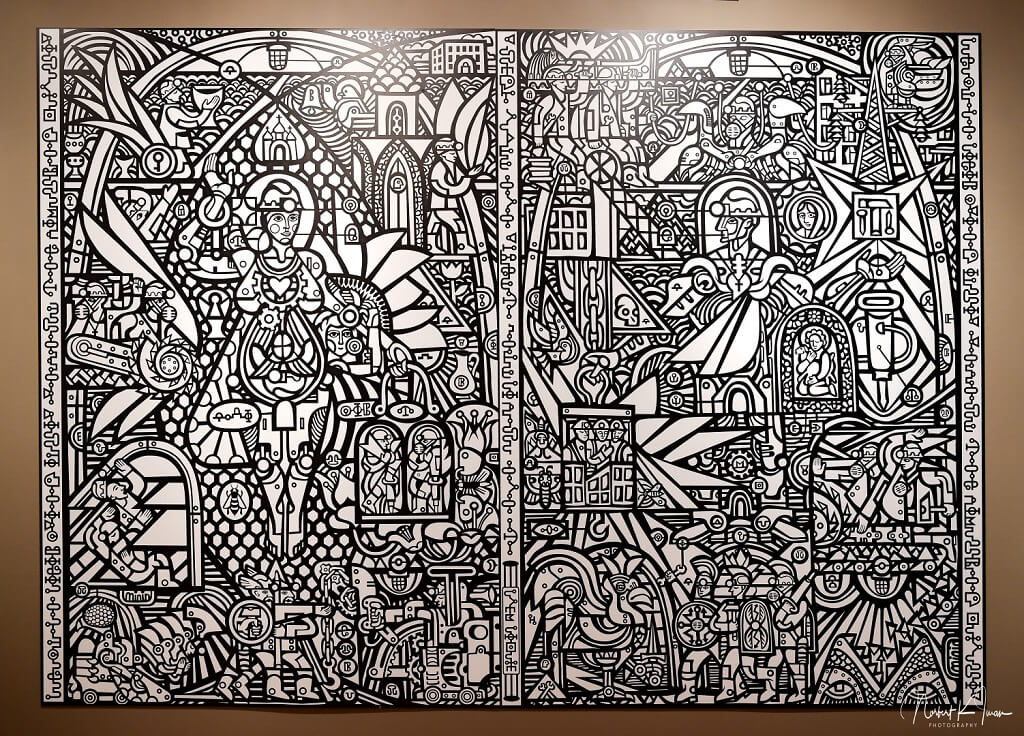

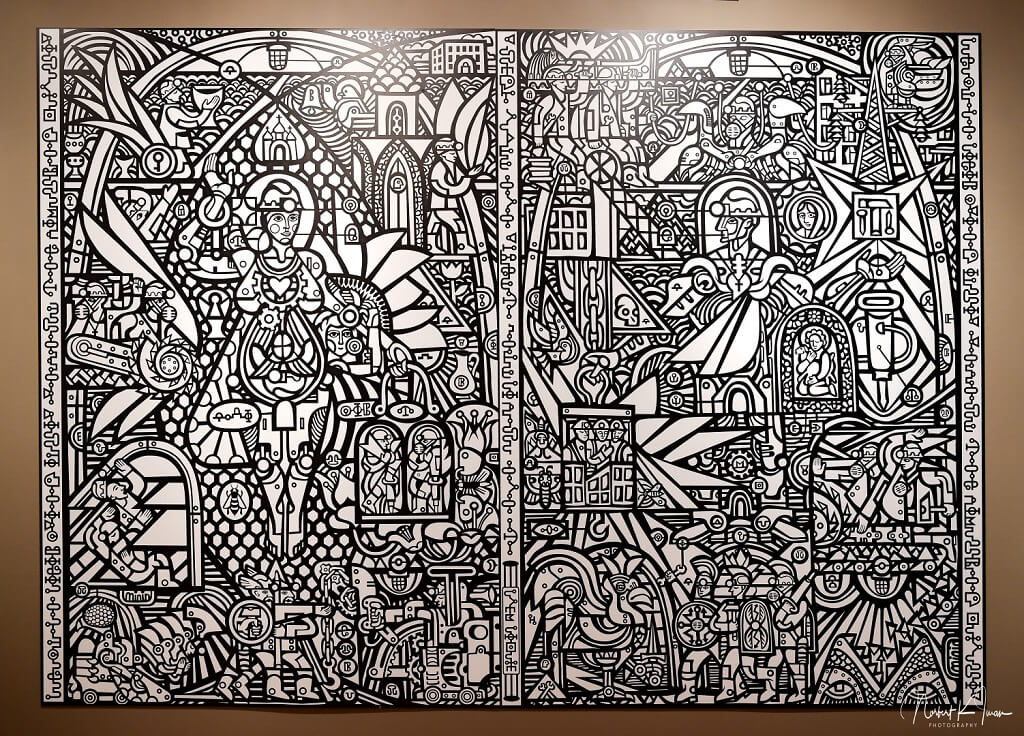

Roman Minin, Plan of Escape from the Donetsk Region, digital art, 2011

Roman Minin’s digital print was produced in 2011. It serves as key image in the exhibition, a reminder of the fact that over two million people have left the eastern part of the Donbas region, which has now been occupied by Russian forces and is ruled by a combination of separatist groups and Moscow-installed military personnel. Of the displaced, a million and a half have moved to Ukrainian cities, while the rest have resettled in various parts of Russia. However, as Minin’s image reminds viewers, already in the years preceding the war many people were contemplating leaving this region, which suffered from industrial decline and corrupt rule. However, people were also aware that this land boasted a colourful past and great natural beauty. Minin’s illustration presents a labyrinth-like image, in which mining personnel and equipment are interwoven with images of nature and architectural treasures. The picture simultaneously reassembles a glass window, a jig-saw puzzle and a video game. It is replete with symbolic forms that require deciphering and negotiating, as if the viewer or “participant” has to understand the situation in order to find an “exit” from the game board. The mechanized masses and the proletarian worker are juxtaposed with the Roman soldier, the mine shaft with the medieval church, the sword with the icon and cross, industrial power with a natural paradise.

The exhibition also contains video installations by Piotr Armianovski and Olia Mykhailiuk.

Armianovsky has already achieved fame as a film director, cinematographer and performance artist. The exhibition presents two short documentary films, entitled “In the East” (2015) and “Me and Mariupol” (2017). He is also known for “Miners’ Stories” (2016) and “Mustard in the Gardens” (2018). Mykhailiuk’s video chronicles a forty-kilometer walk taken in November 2014 by women fleeing from the shelling in Luhansk. She met the women in August of that year, when the railway lines had been blown up around the town of Debaltseve and train travel became impossible. The video is part of her work as a performance artist and has previously been presented in Munich in 2014 and Berdiansk in 2015. It records the experience of real women, all of whom were single mothers, and focuses particularly on the moment when they took the decision to leave.

The exhibition catalogue contains articles by the two curators, the participating artists Yevgenia Belorusets, Olia Mykhailiuk, Lada Nakonechna and Mykola Ridnyi, and the scholars Uilleam Blacker, Oleksandra Gaidai, Olesya Khromeychuk, Ricardo Macias Cardoso, Jean Meyer, Maryna Rabinovych and Vsevolod Samokhvalov.

This is a brave exhibition that challenges the viewer’s perceptions of war. It develops a visual language through which the conflicts of the last six years can be understood, and represents different ideological positions and media responses. When the exhibition opened in Mexico City, it was accompanied by four-panel discussions and fifteen documentary screenings. The response was enthusiastic, with 1,500 visitors attending daily. Commentators were particularly intrigued by the way in which identities have been reshaped during these years by photography, documentary films and performance art. The works in the exhibition bear witness to tiredness in the face of war, but also to endurance and stoical acceptance of routine. They show how anxiety and a desire to protest mingle with self-irony. As the curators point out in their introduction, the works on display deal with the direct impact of military aggression. However, they do so by demonstrating the presence of numerous individual “fronts,” on which battles are conducted and small victories won on a daily basis. In this context “the field of culture” may appear marginal, but in the end has an enduring impact.

The curators Svitlana Biedarieva and Hanna Deikun at the exhibition, 28 February 2020

Share on Social Media